Here’s the bad news right now: On top of everything else on your plate as another year of college kicks off, I’m suggesting you’ve got a little more to do. The good news is that I’ve made a four-year roadmap to save you a little time. While I was doing my summer homework and writing the book, Launch Like a Rocket: Build the soft skills you’ll need for your career by leveraging your entire college experience, I created a spreadsheet for you to save as a copy in your Google Drive or download to use in Excel. Since I’m still proofreading the final layout of the book, I’ll just do a quick post to cover the basics of the planning process to be sure you’re one of the few college graduates with the soft skills needed to succeed. For a quick briefing on soft skills, I like the Bloomberg Job Skills Report for 2016, even though they are talking about MBA recruiters’ wish lists for top candidates. (Master of the obvious: If MBA grads don’t have these skills, imagine how rare college grads with them are.)

Colleges

Our oldest son, Nick, graduated last weekend from University of Puget Sound. I had the chance to hear many students speak on stage at the various award ceremonies and the interfaith service, as well as talk informally at department receptions and parties. I thought it might be worth writing a post before I disappear for much of the summer. The press is full of transcripts and videos every May/June of all kinds of famous, high-achieving people giving inspirational commencement talks. And while I agree with the calls to greatness, the reminders of the problems our society faces that await new eyes and minds, and the warnings that life will be full of challenges, I think some more basic advice on the job hunt and settling into a new place might be useful for new graduates and their families.

You’ve finished college. Not everyone does.

You may have some lifelong friends. Not everyone does.

You may have a job lined up or a graduate school program to start. Not everyone does.

Everyone does move forward from this point and make a life. You will, too. (Be brave.)

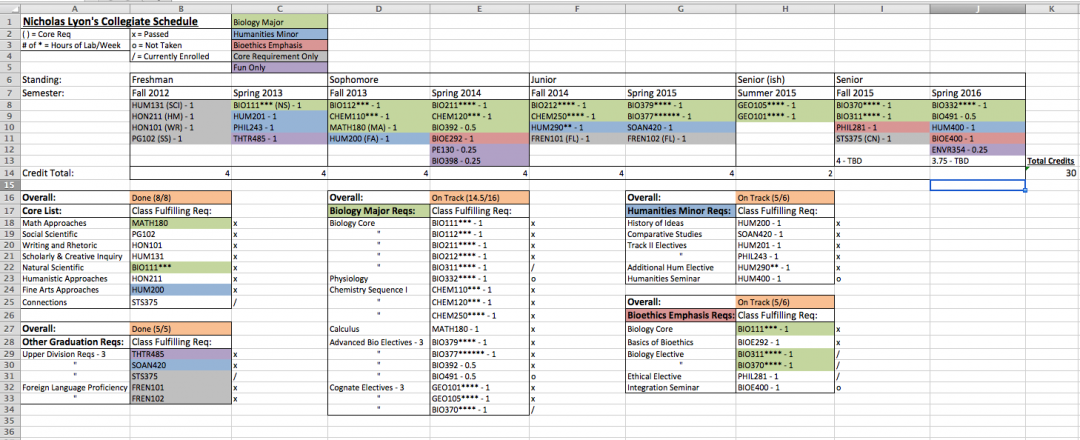

This is the time of year when all the college acceptances start pouring in. You may spend April doing some final visits to figure out which school is right for you now. You may not know what you want to major in, but you likely have a couple of alternatives in mind. It’s not too soon to take a look at the classes your possible schools have and start roughing out a plan. (If you know which one you’re going to go to, you can get more detailed from the start.) This will make college a more valuable, productive experience, and any opportunity to practice this kind of planning will be critical to success in your career. Planning your classes yourself and continuing to rough out the plan as new information becomes available will help you graduate on time and save you a ton of money in the process. (The money aspect may make it tempting for parents to take over this spreadsheet, but if you are a parent who really must, at least use it in stealth mode, to prompt your student to double-check their facts. Land the helicopter and walk away.) It may also save you some false starts. For example, some science majors at some schools are not easily compatible with a semester abroad—taking a look now will help you pick the right school and go in to a chosen school aware from the start about any potential trade-offs between your interests.

By way of example, I thought I’d use one my sons’ college experience. To help you drill down into as much of the detail as you like, without my writing too much into the weeds, I’m linking extensively to the University of Puget Sound website throughout. His journey may be very different from what you imagine for yourself, but the twists and turns of his college career are probably far less than the average experience. The point of adolescence, college, and those first few jobs out of college is to help you figure out who you want to be and what you want to do, so you should expect you’ll need to adjust the grand plan constantly. (BTW, the same thing will be true of your career—see the animation in my last post.)

Luckily, my son, Nick, was willing to send me the College Schedule spreadsheet he showed me over the holidays and said I could share it. By way of background, Nick’s a senior at the University of Puget Sound, graduating this May (2016). He was admitted as a freshman with a Humanities minor and as part of the Honors program. Right off, getting accepted to both programs meant he had to take both program-specific freshman writing seminars (on his sheet these are the HUM classes in freshman semester, although they now have different SSI-1 designations in the link above). Our family thought that was a good thing, because while he was a strong writer and coming out of a large, well-regarded public high school, his classes typically had 30–40 students.

It’s hard for me to resist a book like Excellent Sheep with a subtitle reading “The Miseducation of the American Elite & the Way to a Meaningful Life” and William Deresiewicz delivers right out of the gate. Noting that “Questions of purpose and passion were not on the syllabus,” he drives home the point that students who excel early and consistently enough to even have a shot at the lottery ticket at the so-called elite American universities are fairly uniformly miserable, as with this horrifying quote:

“One young woman at Cornell summed up her life to me like this: ‘I hate all my activities, I hate all my classes, I hated everything I did in high school, I expect to hate my job, and this is just how it’s going to be for the rest of my life.’”

This isn’t an isolated quote of total misery in the book. I’m pretty sure most adults would say if something is that hateful about your life, it’s time to make a move to change things. While most of us well-ensconced in adulthood recognize you might briefly have to stick with a terrible job until you could replace it, I think we’d universally suggest that replacing it as quickly as possible was a good goal.

I knew going in I was going to like this book. As disclosed elsewhere, I’m not a believer in college prices for a vocational education. When it was clear our younger son’s freshman year that his Philosophy class had him all fired up, I remember saying, “Aren’t you lucky? You have the last set of parents in America who want their student to major in Philosophy.” (He is a Philosophy and Economics major while our older son, a Bio major, is a Humanities minor with a concentration in Bioethics. Our dinner conversations will always be interesting!) Even when pre-professional education works, it’s potentially a series of early career successes with a surprising dead-end down the road, when you’re going to have a hard time going back and getting the missing soft skills.

Fareed Zakaria’s book is engaging and passionate. Sadly, when he breaks out the numbers “only about 1.8 percent of all undergraduates attend classic liberal arts colleges like Amherst, Swarthmore, and Pomona.” (Good news if you are one of them and can make the pitch to hiring managers.) He gives a clear, concise overview of the history and purpose of liberal education in America, “The essence of liberal education was ‘not to teach that which is particular to any one of the professions; but to lay the foundation which is common to them all.’” Given how much the world is changing and how little we can predict about the future jobs needed, that seems like the safest plan to me. (Yes, you’ll forgo the six-figure Google CompSci gig right out of college, but life and careers are long, plan accordingly.)

Mr. Zakaria quotes many influential and successful professional reflecting back on their liberal educations, including Norman Augustine, former CEO of Lockheed Martin, who says “I have concluded that one of the stronger correlations with advancement through the management ranks was the ability of an individual to express clearly his or her thoughts in writing.” As to the author’s own education and the emphasis on articulate communication, he concludes “In order to be successful in life, you often have to gain your peers’s attention and convince them of your cause, sometimes in a five-minute elevator pitch.” (The book jacket notes “Fareed Zakaria has been called ‘the most influential foreign policy advisor of his generation’” by Esquire Magazine, so I’m feeling confident he’s an ace at convincing people of his cause.) And, just so you don’t think we’re ganging up on you in pursuit of a different kind of “liberal agenda:”

“In 2013, the American Association of Colleges and Universities published a survey showing that 74 percent of employers would recommend a good liberal arts education to students as the best way to prepare for today’s global economy.”

Recommendation? Essential if you or your student is still in the process of choosing a college. If in college, I still recommend as I think you can supplement a pre-professional set of academic requirements with electives to round out some of the missing pieces. If you’ve already graduated, it will make you aware of some weaknesses you may have. That’s not a bad thing to know with all the great online and local extension classes available at a free or inexpensive price point to get you to fill the holes before you start to wonder why your fast-moving career has stalled out.

At the end of September I was back at Denison University for parent and homecoming weekend. As part of the fall weekend, the Career Exploration department always organizes a series of roundtables for particular careers. Last year I covered communications, but this year I figured that the Arts roundtable was bound to have students I could help advise. I always enjoy these discussions with students because it sparks so many new ideas for me. While I didn’t think Reid Hoffman’s book quite hit the mark since his focus was more on managing your career, making the “Start-up of You” a metaphor, my takeaway from my roundtable experience is that everyone literally should be thinking about their business(es). (And as I read more about Mr. Hoffman’s thinking, I think we might be in agreement, after all.)

For arts students it’s perhaps more obvious that this is required. While one student I met seemed more interested in a career as a recording artist, for which I have little advice, it was clear that he also had the skills to compose music, so my follow up email was about the various royalty-free sites where we buy music for many of our films. Essentially an Etsy-like business model, I don’t know why any music student wouldn‘t put some tracks up and start learning what sells and what doesn’t. Although this may not be enough to earn a living and it may not be their ideal career path, what if it could ultimately generate $300/month in income? (With a limited consumption of time, and all that time consumed when most convenient to them.) Add in one wedding-type performance event a month (always a weekend) with perhaps four people splitting $1,000. Again, very little time given up in exchange for part of a monthly income stream. Build up a following via the royalty-free music and maybe once a month you can sell a custom composition for a corporate film for $1,000. You see where I’m going, right? Something has to happen before you’re an overnight success with millions coming in.

Dan Chambliss and Christopher Takacs followed over 100 students over eight years at Hamilton College to see what works and what doesn’t. They show the reader how college works and see beyond the four years, with frequent commentary from alumni looking back at their college years and with insight into what choices paid off and what opportunities they missed. While they are researchers writing for an academic audience, and the book is a little dry, with more information about background methods than the lay reader wants, the core is a very reliable, persuasive guide to what needs to happen for a successful college experience (and if college isn’t successful, you’re unlikely to have a successful post-college launch, right?)

Interestingly, students don’t need to find a large group of great people—they need just a few—and those can come from nearly anywhere on campus. But those friends are crucial to success on all levels. And, although probably true all through life, it’s interesting to consider that friendships within one group may preclude friendships with other groups—whether due to time constraints or clannishness.

My work neighbor, UC San Diego, is launching a program to support graduate students. Keeping in mind that research universities’ missions are focused on professor research, then graduate students, and after that undergrads, this is an idea I could see really taking off through all kinds of schools for all kinds of degrees.

Odds are you’re not at UC San Diego, so how can you access these kinds of opportunities, whether working on a bachelor’s degree or a graduate degree? Their plan has a four-fold approach:

- Career Nights

- Certification in leadership, teamwork, and project management

- Communication workshop

- Career Services expanding their offerings to include grad students

These are pretty simple to replicate with some initiative on your part.

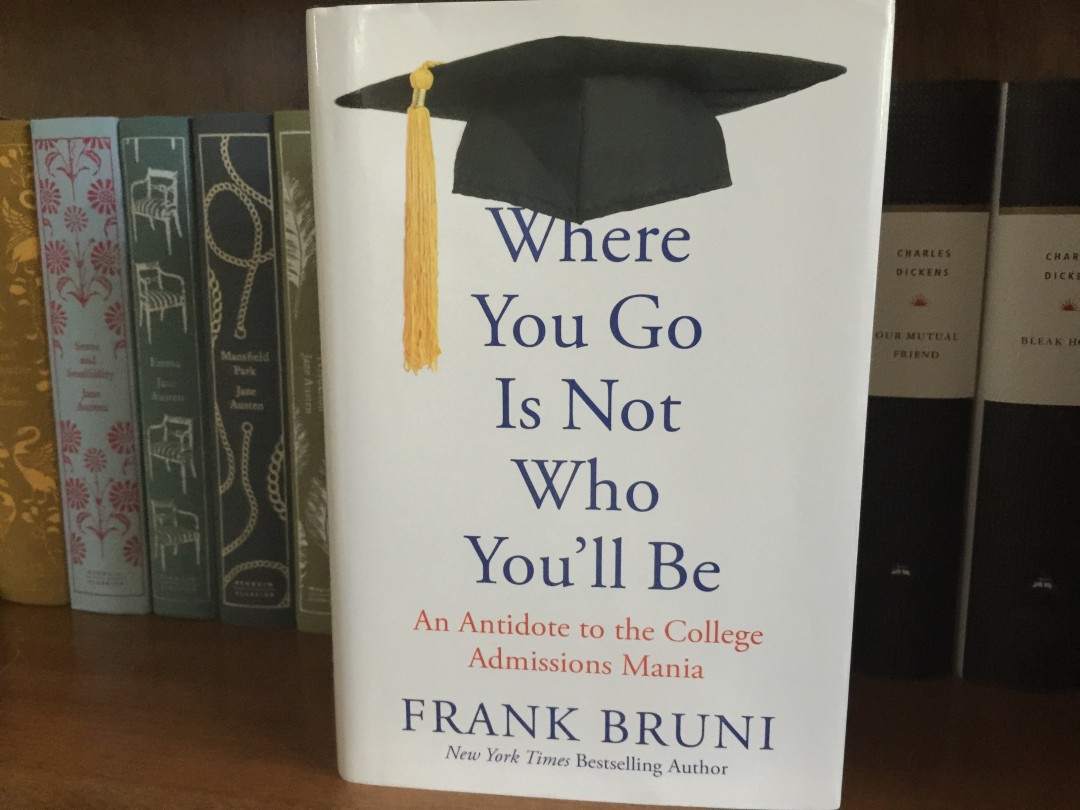

It seems every book in this college and career genre has a subtitle. Frank Bruni’s excellent book is subtitled: An Antidote to the College Admissions Mania. (I’m not sure it’s as prescriptive as all that.) As is probably clear by now, I’m not a big believer in name brands. Naturally, I’m going to have come to the college admissions process as a skeptic after years in advertising. So I agreed with Mr. Bruni’s message, although perhaps for different reasons. Much of the research he quotes were things I’d encountered elsewhere before my sons were looking at colleges and it had influenced their decisions. The book is full of examples of amazingly successful people who went to schools you’ve never heard of because those schools were near home, offered scholarships, or had unique programs that would let them develop as human beings.

In discussing Google, quoting an article by fellow New York Times writer Tom Friedman, Bruni writes “…in an age when innovation is increasingly a group endeavor, it (Google) also cares a lot about soft skills—leadership, humility, collaboration, adaptability and loving to learn and re-learn.”