As some people on the internet know, one of my sons is a pro gamer. Clicking the links in and about Jake’s Twitter account I’ve been fascinated to see the new Overwatch League launch. While both my sons learned a lot about business from growing up in our house, I can see in speaking with Jake that even a high level of exposure doesn’t give you a perfect grasp on the practical vocabulary of working. There’s a whole other book in here, but I’m going to start with some posts as a warm up exercise. I’ll bold words I explain in the larger discussion because these are the working vocabulary you need to have to manage your working financial life, whatever you do.

First off, an employee gets a salary so when the new Overwatch league launches, all players will be salaried. What that means is that an employee gets a paycheck from which their share of taxes have already been subtracted and remitted to the government. There is another share of taxes covered by the employer—basically a matching amount for the employee’s line item deductions for FICA (social security) and Medicare. Together those are about 8%. Salaried employees (vs hourly), also typically have paid holidays, vacations, and sick pay. In California (and some other states), your paycheck also has you pay into state disability (SDI on your paycheck stub), which covers you when you are disabled for a short period of time (more than a week, less than a year). And your employer also pays taxes that provide unemployment insurance, so if you are laid off, you can collect a small portion of your pay as unemployment compensation while you find a new job. You might have to clock in for some hourly jobs, but in general, you get your paycheck without taking any triggering action other than showing up and doing your job. Being an employee is a nice way to start a career, because you’re dealing with so many other things as you launch professionally that setting up a business might not be the first full-time working experience you want to take on.

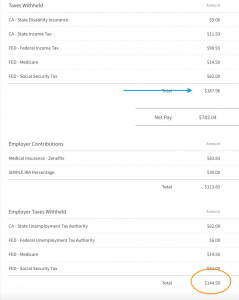

I can’t speak to all the current contracts out there, but many gamers under contract are paid as independent contractors. In contrast to an employee, a $1,000 biweekly contract for an independent contractor would result in exactly $1,000. (Likely you need to invoice regularly to trigger the payment.) The IC is responsible for setting aside money to pay taxes, both income and payroll, including the employer’s share of payroll taxes. Here’s a screen shot of an example paycheck in California (run through our Zenefits account, so that’s why the medical insurance says Zenefits).

You can see at the bottom in the orange oval that the employer share of taxes is $144.50. This is a sample from early in the year—the unemployment taxes are calculated on a low base number, so they disappear partway through the year. The blue arrow higher up shows you the $187.96 in taxes that’s being remitted for the employee from their own funds. In this case the employee is saving 3% of their paycheck into a retirement account and getting a 3% ($30) match, as well as having their health insurance premium covered and you see that in Employer Contributions. An independent contractor gets the full $1,000, so they have to have the discipline to set aside the $188 in employee tax deductions and the $145 in employer contributions. And they also need to pay for health insurance and save for retirement. For the employee, saving $30 for retirement results in $60 being put in their retirement account.

BTW: No matter what the stock market does, the employee just doubled their money simply by saving, which is why 100% of the financial advice columns almost no 20-year-old reads say to always max out your retirement contribution to get at least the full employer match.

So why would anyone choose to be an independent contractor? The employee is getting $1200 for the same $1000 worth of labor.

The employee in our example has a total take-home pay of $782 on the $1,000 gross amount. There was another $30 they willing saved for retirement to get the match, so I’m going to add that back in. I’m going to ignore the health insurance and free $30 employer SIMPLE IRA contribution, and to keep the math simple, we’ll say the compensation is $2,000/month (more money puts you in higher tax brackets, so the percentages would go up for higher amounts), or $24,000/year.

Employee: 1,000 – (782+30) = $188 (18.8% tax rate)

Employer: $144.50 (14.45% tax rate)

18.8 + 14.45 = 33.25% tax rate

On $1000 with a 33.25 rate = $332.50 in taxes, but the employee only covered $188.00. Over the course of the whole year we multiply that by 24 and we get $7,980, of which the employee paid $4,512. (Again I’m oversimplifying—in many cases you get paid every two weeks, which means you get 26 paychecks in a year, and the exact rates of your tax deduction depend on what information you put on your w-4 when you get hired.) Employees get a w-2 from their employer at the end of the year. A w-2 is a tax form that summarizes all of the pay stub information and a copy is also sent to the relevant government tax agencies.

The key here is that at the end of the year both tax returns would have similar tax rates, but the employee’s return is going to show that they have paid close to the right amount of taxes already. Here’s where it gets interesting in the US: Independent contractors get to write off a lot of business expenses that employees can’t easily deduct. An esports athlete, for example, would definitely be able to say all of their professional gear was a business expense, including all hardware, software (like Steam), as well as subscriptions to things like Twitch.tv. They likely could write off their internet service, mobile phone, tickets to competitive events and conferences (BlizzCon) (including all related travel such as airfare, mileage, hotel, meals during the visit). While your employer might send you to a conference and cover those expenses, they are unlikely to give you the exact PC, mobile phone, and internet service you want, if they give you any of those things at all. So the independent contractor is going to take their $24,000 and deduct all their business expenses. Let’s say that they had $9,000 in expenses over the year. They would then have taxable (net) income of $15,000, and pay 33.25 in taxes, or $4,987.50.

Look back up to compare the teal tax numbers and you can see the IC ended up paying a lot less in overall taxes, but without an employer to cover the employer share, they actually end up paying about $475 more. In the process they got to have all these other things, some of which, the mobile phone and internet, everyone seems to have and pays for with after-tax dollars. The employee still has to buy those things with their net pay (same thing as take-home pay). At the end of the year all of an independent contractor’s clients will send them a 1099, a tax form that is also copied to the relevant tax agencies. Companies are required by law to send these, but if your clients are individuals paying with checks or credit cards, know that tax agencies can also look at your bank records, so you still need to declare your income accurately. (If you are getting paid in cash, and the money is small, as with middle-school babysitters, you are actually breaking the law by not declaring the income, but it’s statistically unlikely you’ll get caught. It’s simply not worth the IRS’s time to audit a random subsection of suburban 12-year-old girls to get their share.)

I’ve simplified many things here, but the main objection to this analysis is that industries that make extensive use of independent contractors to supplement their workforce typically pay them more than employees. This is to partly cover for the missing employer taxes, but it also compensates ICs for the shorter-term nature of the work, the lack of benefits, and the fact that ICs don’t just show up, do 40 hours of work in a week, and get paid. They have to write proposals, sell work, do the work, do the bookkeeping, invoice, follow up on late payments, and buy all the tools of their trade, so they either have to work 60 hours a week to bill 40 or accept that in 40 working hours they will only have 25 billable hours. Like all small businesses, it’s up to them to set their rates at the optimal price—one that is low enough to attract sufficient customers, but high enough to make their business a viable career option. When you pay for any service you might occasionally buy (e.g., an oil change, dental cleaning, a massage, takeout food), you pay more per unit purchased than the cost because you are paying for the convenience of buying a portion of a professional’s working hours. It’s more efficient to for a person to sell all their professional time to one buyer, so if you’re going to find all those other buyers and service those accounts you need a premium for it to make sense to provide the buyers with the convenience. That’s why businesses bill their employees out at rates much higher than they pay the people—Jiffy Lube is charging for brokering the oil change transaction. And Twitch.tv pays the gamer less than your subscription price for the same reason.

I do want to note that independent contractors are required to make quarterly estimated tax payments—even their first year in business—and the IRS and your state will tack on penalties if you fail to do so, which raises your effective tax rate.

Running a creative business, all employees on the creative side have skills and their own equipment, and if a project is too small for us at LYON, we’ve been known to hand it off to current or former staffers, so they can sell their Saturday and make a little extra cash. For employees who’ve left us to move away and start their own company in another city we’ve typically been their first customer, and a large one for a period of months. It helps us cover their absence as we get a new employee fully up to speed, and gives them a runway to go out and line up work in their new home town. In recent years, the side hustle has given everyone a chance to play this game. Of course, the side hustle only makes sense if you do actually make money (net profit), but it doesn’t have to make much if it is also moving some current after-tax expenses to the pre-tax side of the equation.

Just be sure when you’re talking about a new job or gig, that you understand the implications of simple words like salary and independent contractor, so you can be sure your negotiated compensation is a good deal for you.

No Comments