This is the time of year when all the college acceptances start pouring in. You may spend April doing some final visits to figure out which school is right for you now. You may not know what you want to major in, but you likely have a couple of alternatives in mind. It’s not too soon to take a look at the classes your possible schools have and start roughing out a plan. (If you know which one you’re going to go to, you can get more detailed from the start.) This will make college a more valuable, productive experience, and any opportunity to practice this kind of planning will be critical to success in your career. Planning your classes yourself and continuing to rough out the plan as new information becomes available will help you graduate on time and save you a ton of money in the process. (The money aspect may make it tempting for parents to take over this spreadsheet, but if you are a parent who really must, at least use it in stealth mode, to prompt your student to double-check their facts. Land the helicopter and walk away.) It may also save you some false starts. For example, some science majors at some schools are not easily compatible with a semester abroad—taking a look now will help you pick the right school and go in to a chosen school aware from the start about any potential trade-offs between your interests.

By way of example, I thought I’d use one my sons’ college experience. To help you drill down into as much of the detail as you like, without my writing too much into the weeds, I’m linking extensively to the University of Puget Sound website throughout. His journey may be very different from what you imagine for yourself, but the twists and turns of his college career are probably far less than the average experience. The point of adolescence, college, and those first few jobs out of college is to help you figure out who you want to be and what you want to do, so you should expect you’ll need to adjust the grand plan constantly. (BTW, the same thing will be true of your career—see the animation in my last post.)

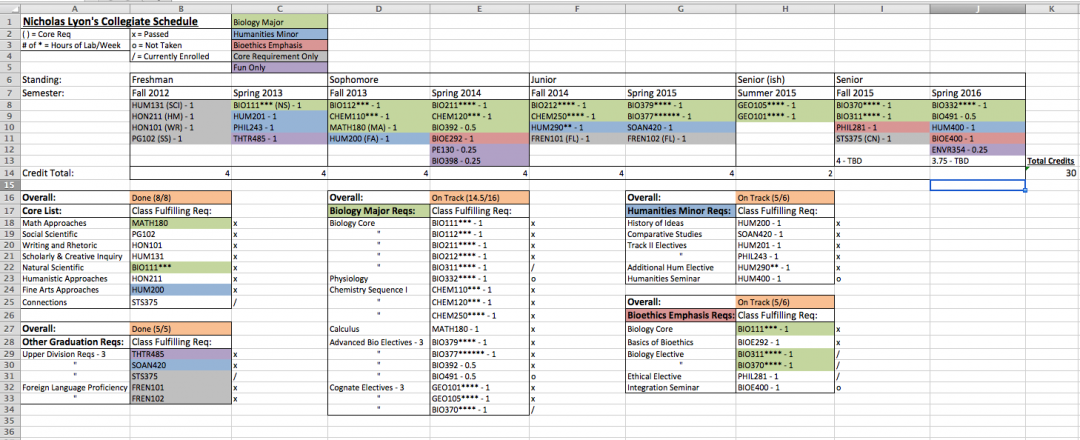

Luckily, my son, Nick, was willing to send me the College Schedule spreadsheet he showed me over the holidays and said I could share it. By way of background, Nick’s a senior at the University of Puget Sound, graduating this May (2016). He was admitted as a freshman with a Humanities minor and as part of the Honors program. Right off, getting accepted to both programs meant he had to take both program-specific freshman writing seminars (on his sheet these are the HUM classes in freshman semester, although they now have different SSI-1 designations in the link above). Our family thought that was a good thing, because while he was a strong writer and coming out of a large, well-regarded public high school, his classes typically had 30–40 students.

He quickly declared as a Biology major and that was the driving force behind his planning. Just the fact that an 18-year-old freshman came up with the idea of this spreadsheet and kept it going probably tells you a lot about him. But we realize you may not be that obsessively organized or feel a need to formulate a theory and then test it, so you can download the sheet and adjust it easily for your plan. (Thanks, Nick!)

So far, so good, freshman year his plan was really just helping him line up the right classes and potentially serve as a rough agenda in conversations with his advisor. Puget Sound, like most SLACs, doesn’t have a hard time getting students into a full load of classes each semester, all of which they want or need, but students don’t always get all their first choices in a given semester, so seeing how decisions ripple through the whole plan, particularly given that upper division courses have prerequisites, is key to graduating on time.

Sophomore year was pretty smooth academically for Nick, chugging through the classes he needed, which also helped to test his commitment to Biology. If a semester like his Spring 2014 sounds like fun, then you, too, are probably a science major: Biology 211 (General Ecology), Chemistry 120 (second half of General Chem), Biology 392 (Intro to Research), Biology 398 (quarter-credit Seminar Series), Bioethics 292 (Basics of Bioethics), and quarter-credit PE130 for Scuba certification. The intro to research was a class was a prerequisite to help writing his summer research proposal to get funding for his independent research.

But then he had a new wrinkle. His junior year Puget Sound rolled out a Bioethics emphasis. Nick really wanted to add this, but realized it was going to be impossible to fit all the requirements into his remaining time. He was able to convince the program (gotta love a small liberal arts school where a student can get straight to the decision-maker for a pitch meeting) that Conservation Biology (BIO370, fall 2015, his senior year) should count for Bioethics as well as for Biology. Science students in the Bioethics concentration are warned that “only one scientific elective may count unless special exception is granted from the Advisory Committee.” (I have no idea how you figure out what might be a special exception or who the advisory committee is, and the degree requirement webpage footnote gives you no more info, but that’s exactly the kind of thing you future boss is going to hire you to do, so you might as well find the contact and make the appeal.) Planning out the rest of his time, given this new concentration, he realized something had to give and decided that he would drop the Honors program. The lure of Honors from his high school vantage point had largely been writing a senior thesis, but he was far enough into Biology to realize he’d be doing that anyway, based on his summer research. He also realized he’d need to do some summer school after junior year to fit in all the new requirements and was able to check in with his underwriters (that’s Mark and me) to confirm that supplemental funding was available. He wanted to further expand his sophomore summer research over junior summer, but Puget Sound has a policy of either/or about summer school and research scholars. His Biology professors were willing to fund his small hard costs out of the department budget so he could do it on the side, but encouraged him to apply again for a research grant, saying they’d go to bat to vouch that he was the rare student who could handle doing both in one summer. Sure enough, he was funded and approved for both that summer.

None of this comes together so beautifully without long-term advance planning. You need to look ahead and see the roadblocks, anticipate some solutions, and probably jump through some hoops to get approval. (Tip #401 for talking to a future boss or team: Don’t come to the table with just the problem, show up with the solution in hand.) While your interests and school may be completely different, you can see how having a plan that continued to evolve meant that Nick was able to maximize his opportunities to explore his evolving interests. And while we’re proud and happy he’s graduating on time and has a plan for his future, as well as some backup plans, I think that the experience of his college academic career has been as valuable as the content.

PS: The second tab Nick added junior year, when he realized graduate school was part of his long-range plan and he wanted to calculate not only his current GPA, but project out his cumulative as each semester progressed. Like most college students, his early grades were good, but not all As, so he really put the pressure on to raise his cumulative GPA, so he could focus his energies if he encountered any obstacles. We left it in place, in case it’s useful for you, even though it’s not anything I discussed.

April 2017: A related post on how planning worked out for my other son, Jake, for very different reasons.

No Comments